My grandparents settled in the Mangaweka area in about 1896. My family were sheep farmers. I was born in 1949, but we lived a life that was a whole generation behind. When I was ten, we moved to a remote area at the head of the Kawhātau Valley, about twenty-five kilometres from Mangaweka. It was a wonderful childhood. I had three sisters, and we were homeschooled. We would order bulk stores – the things we couldn’t produce ourselves. We had a woodrange and rainwater. The hardest part was probably no refrigeration. Dad would kill a mutton, and we’d be frantically eating meat every meal so it didn’t go off.

I met my husband-to-be, an Australian, when I was seventeen. He was working for the New Zealand Forest Service in the Ruahine Range. His name was Henry Dorrian, and he was a character. He passed away over ten years ago now. Like me, he had a deep appreciation of the New Zealand bush. We married when I was eighteen and moved into the village of Mangaweka in the early seventies.

It was through my children – three boys and three girls – that life in Mangaweka village really happened for me. I was quite shy, and I grew up with my children. We became very involved in Playcentre, school committees, and Guides and Scouts. In those days, there were a lot of children in Mangaweka, and they all came to our house! Those children are still my children’s friends and my friends. It’s part of the Mangaweka magic. It’s the pull to come back. It’s the look of the Papa Cliffs, and the fact that you can sit by the river and let it sweep your troubles away. It’s the people who come to your rescue if you need help. During times of stress, death, accidents and sickness, the village really comes into its own. That’s what Mangaweka magic is – the belonging.

It was about the early eighties that the housetruckers came in and bought properties. There was also a big influx of workers while the new state highway and new railway went through. When it was all finished, they up and left. One or two families had been bitten by the Mangaweka magic and stayed on. It took a few forward-thinking people to put us back on the map. John and Viv Eames put the DC-3 in Mangaweka, and we became known as the place with an aeroplane on the main road.

I worked for the Department of Conservation once the children started to grow up. Possum monitoring and weed control made me passionate about the bird life and the bush. We have a podocarp forest with rarities like Celmisia ‘Mangaweka’ – a little daisy we’ve been fighting to protect – and Dactylanthus, or wood rose. It has an increasing population of falcon, lots of wood pigeons and tūī.

I compiled a centennial booklet in 1984, written by a lot of different people. It started my whole passion for the history. The village used to be called Three Log Whare, when the surveyors were coming through for the railway line. In the early days, when they were doing earthworks around here, they dug up a whale skeleton. In the Papa Cliffs you can find whole mussels and pipi beds, fossilised and growing on top of one another. Mangaweka Heritage Trust runs a small country museum. It tries to protect some of the buildings and promote Mangaweka. There’s a cantilever bridge across the Rangitīkei River, which is the only one of its design in New Zealand. We recently saved that from demolition.

The Fakes & Forgeries art festival happens every two years. Richard Aslett owns the “Yellow Church” Art Gallery, which was the old Presbyterian church. He hit upon the fact that Karl Sim – who was found guilty of forging some of Goldie’s works – lived in Mangaweka as a child. People are asked to submit a copy of a famous painting that’s got a Mangaweka feel about it. The place that looks like a barber’s shop used to be the electrical shop. It’s now our mailroom – one of Mangaweka’s meeting places. We’ve got a set of shelves, which are our “sharing shelves.” When somebody’s got too many cabbages or plums, they get left on the shelves. Or a book that they enjoyed reading – they just pass it on.

Mangaweka still has a primary school, but recently the school lost a lot of pupils. We were in danger of losing it altogether. The school is the heart of the community. Eighteen months ago it had seven pupils; soon it’ll have about twenty-three. The population of Mangaweka is about 200. It’s the same now as it always was: if you want something done, don’t sit around waiting for somebody else to do it for you. Just do it!

This story appeared in our Takurua Winter 2023 Edition.

Related Stories

“The Region-off is so great because it allows kids to get a foot in the door”

This year, Emma Poole, 28, became the first woman to win the prestigious FMG Young Farmer of the Year Competition in its fifty-five-year history.

Ailie & Nina

Ailie and Nina are two sisters on the cusp of returning home to Canterbury to lease their family farm, nestled in the foothills of Mount Somers.

Leading with Care

Dawn has had a long career in governance – often in male-dominated environments – from local community groups to national boards.

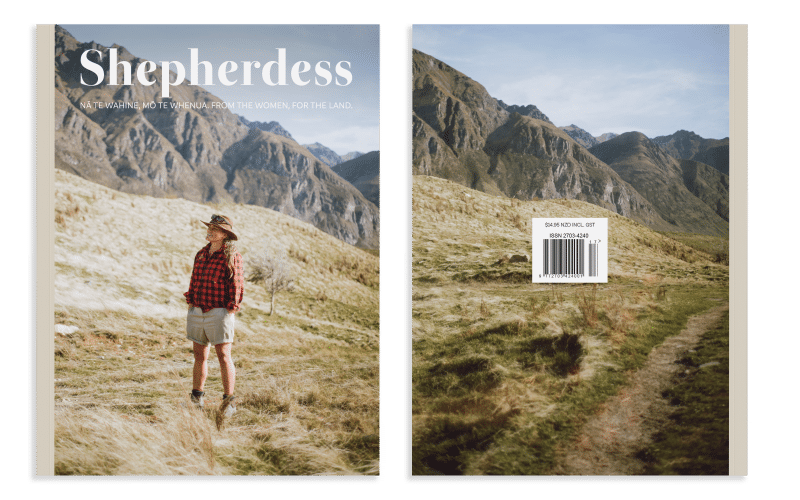

Out Now

Seventeenth Edition

Our beautiful Ngahuru Autumn 2024 Edition is out now!