I grew up in the southern Coromandel in the Karangahake Gorge between Paeroa and Waihi on a lifestyle block. My parents both worked – my dad was a science teacher; my mum was a nurse. We had a few animals and a forestry block.

One of my earliest memories was digging in the large veggie garden out the back of our log cabin house. I remember the soil being really red and finding it full of worms. My dad constructed a compost bin and we always had a ready supply. We planted an orchard – plums, Golden Queen peaches, nectarines, nashi pears, lemons, feijoas. My mum’s love language is food. When we were kids, she would preserve masses of peaches and nectarines. Our cupboards were always full of jars of fruit – even in the bathroom! She still cooks and bakes for us. Now that I’m working full time with three kids, she often drops off a meal to help us during the week.

Many New Zealanders’ experience of food is going to the supermarket. And I also shop at the supermarket, but we have huge potential to integrate food production back into our cities. For one hundred years or more we, like many countries around the world, have actively zoned food production out of our cities – it’s too complicated, land prices are too high, animals are a nuisance – even though food is an essential component of life. Aotearoa is a food-producing nation, yet we’re relying on this long, global food supply even though we produce enough calories to feed forty million people!

The peri-urban zone is a descriptive word for talking about the edges of our cities. And it’s notoriously difficult to define because as cities grow, those boundaries move in sync with urban expansion – so the land in this zone is continuously under pressure. What’s happening is our cities are located on some of our most fertile soil and, as they grow, we’re losing that resource for future generations. Once it’s gone, it’s gone.

When I started researching this area, I realised that when you consider life’s essentials, we’re very good at designing for shelter, water and air quality. But when it comes to accessing local food – we seem to completely ignore it from an urban design and city planning perspective. About four years ago I started working with the Centre of Excellence – Designing Future Productive Landscapes at Lincoln University as part of my academic role. I was asked to look at future opportunities for one of the university-owned farms, which sits only three kilometres from the edge of Rolleston – a fast-growing satellite town on the outskirts of Ōtautahi Christchurch. What we came to understand was the huge potential peri-urban farms could have for reconnecting urban folk with the land and with food production.

We’ve since completed a large survey with residents living in that peri-urban zone – and fifteen key themes came through about people’s aspirations and concerns. One was to create a low-impact farming belt around urban areas – producing food to serve that local community. I think we’re at a point where people want to connect with where their food comes from. I’m certainly more aware now about where much of our food comes from. When you look at the place of origin stickers on packaging it can be really confronting. This was one of the key findings of our research – people are wanting to be able to easily access locally produced food.

I sit on the board of Roimata Commons Trust, which was originally set up as a community garden and pātaka kai in Radley Park in Woolston. It’s wonderful, a real centre for the community to gather for events, workshops and the like. We now also run an organic kai box delivery service called Toha Kai to provide boxes in lower socio-economic areas of Ōtautahi with fresh organic produce. Next, we’re starting a farm that sits in the peri-urban zone. It’ll be an organic market garden that will produce the kai to go into the boxes.

With my family, we try to grow what we can. It’s been a real learning curve. The kids are on this journey with us. We’ve learnt how to farm sheep for lamb, and that our hill property is not suitable for cattle; where we can and can’t grow fruit trees, as our property is very exposed to the strong, cold easterly winds. We’ve also learnt that growing food close to the house will ensure much more regular maintenance! We’re still learning and watching the seasons here.

Glossary. Pātaka kai, storehouse/pantry.

This piece is the sixth in a series supported by the Our Land and Water National Science Challenge. Shannon Davis led research that developed five ways to rethink the border between city and country. Read more at Our Land and Water.

This story appeared in our Takurua Winter 2023 Edition.

Related Stories

“I had to innovate or die.”

Laura Koot, 36, founded agritourism business Real Country to share a taste of “real, rural New Zealand” with her guests.

Cecelia & Jessica

Jessica and Cecelia are best friends and bull beef finishing specialists on Rangitaiki Station, a Pāmu farm, about fifty kilometres southeast of Taupō.

The short course full of “useful little gems” to help identify stress and prioritise wellbeing in yourself and others

Alice Trevelyan, 33, completed the ‘Know Your Mindset. Do What Matters’ programme with her husband, Dave.

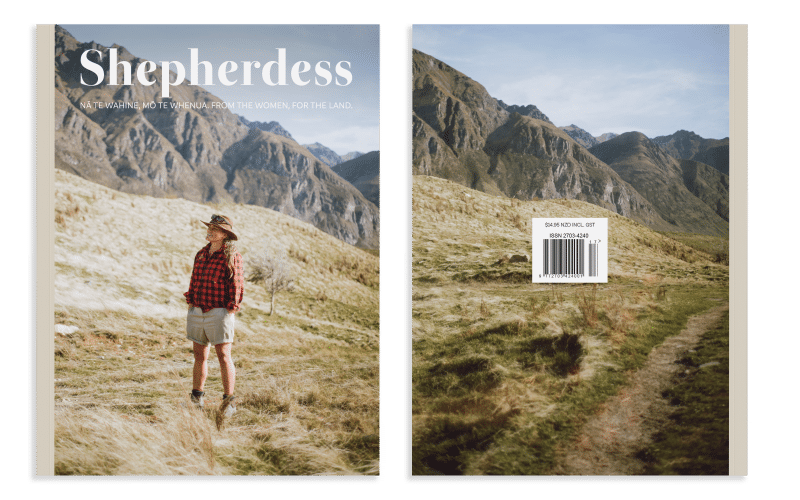

Out Now

Seventeenth Edition

Our beautiful Ngahuru Autumn 2024 Edition is out now!