For me, water is a physical representation of our whakapapa - to Papatūānuku, to Parawhenuamea and to the many kaitiaki of our waters. When we meet people we say, "Ko wai koe?" and what we are asking is "Who are your waters?" I spent my early years in Tūranga Gisborne, close to my whānau in Ngāi Tāmanuhiri and Ngāti Porou. And then we moved to Turangi just before I started intermediate school. I spent the rest of my time in Tūrangi with my mother's family of Ngāti Tūwharetoa. I have only ever grown in my own takiwā, which is a very privileged place to be.

Swimming in my ancestral river, the Tongariro, with my cousins, in the waters that my grandmother swam in, and her father and his mother, through multiple generations, is a humbling experience. Our role as kaitiaki to our waters is inherent in that whakapapa. I've always been motivated by the understanding in my hapū, Ngāti Tūrangitukua, that the rivers and our lands had been confiscated for the hydropower development in Turangi. We always knew waters had been stolen from other iwi by the Crown and diverted through our awa, causing a deep mamae associated with the Tongariro River. The impact of the hydro scheme on our waterways was traumatic and intergenerational. Confiscations happened in our hapū in the sixties, not in the 1800s. These takings were in the lifetimes of my grandmother and my mother. Our waters suffered deeply. That was the most important lesson I learnt, and why I became an environmental planner.

I am not an academic. I am just a practitioner. I am a person who works with whānau. Ultimately, I think I became a geographer so I could go into waterways and do stuff on the whenua. I was blessed to have spent my formative working years within Ngāti Tūwharetoa tribal entities on and off across a decade. That learning then enabled me to work for other iwi including my own whānau in Ngāti Porou, and to have opportunities in the corporate space. Much of this has been advocating with developers and councils for hapū and iwi perspectives in resource management, an often very inequitable space for tangata whenua. It's about making sure that the Crown and councils are honorable Te Tiriti partners, so we have a place in decision making for our taiao. I feel an obligation and responsibility to do the work well. And the pressure of not getting this wrong.

At its simplest, Te Mana o te Wai reflects the importance of the health and wellbeing of wai. It is a transformative concept that enables us to put the well-being of the water first. The approach is not new, but weaves traditional thinking from te ao Māori into the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management 2020. Our fundamental view is that we are of the environment and not in dominion over it. This is core to how we must change the way we live, how we deliver sustainable economic solutions and how we centre our environment, rather than selfishly centring ourselves.

Te Mana o Te Wai asks, "What does the water need to be healthy and well?" The first right of water goes to water - to sustain itself, to look after the ika and the taonga species within it. And to have the flows it originated with. Mana whenua must define and continually inform what Te Mana o te Wai means for each river and lake. Once the health of water is provided for, then we can determine the quality and quantity of water available for human health, followed by the well-being of people and communities.

It requires people to think about the water as a living, breathing taonga in its own right that needs to be looked after, rather than a commodity to be taken until it is gone or pushed to its limits until it can no longer survive. It is about operating from a place of abundance, not abstraction.

We can live wonderful, rich, healthy lives without exploiting our waterways. I call myself a capitalist hippy. Tangata whenua are multidimensional beings, we can hold multiple roles at once. We can be kaitiaki and entrepreneurs and cultural experts at the same time. The wealth of knowledge that resides in the hearts and minds of hapū and iwi will help us create a society that puts its natural environment at the core, that values relationships and connection, and creates opportunities for our mokopuna. That's something I think we can all support, no matter your upbringing.

Glossary. Awa, river. Hapū, kinship group. Ika, fish. Iwi, extended kinship group. Kaimahi, practitioners. Kaitiaki, steward/s. Kaitiakitanga, stewardship. Mahi, work. Mamae, ache. Mana whenua, iwi or hapū who have rights to make decisions about that area, their whakapapa links them to that area. Mātauranga Māori, Māori knowledge. Mokopuna, descendants, grandchildren. Papatūānuku, earth mother. Parawhenuamea, mother of water. Takiwā, tribal territory. Tangata whenua, people of the land. Taiao, environment. Taonga, treasure. Te ao Māori, the Māori world. Te Tiriti, the Māori-language version of The Treaty of Waitangi. Wai, water. Whānau, family. Whakapapa, genealogy. Whenua, land.

To understand more about how iwi, hapū and regional councils will be implementing Te Mana o te Wai, see ourlandandwater.nz/te-mana-o-te-wai.

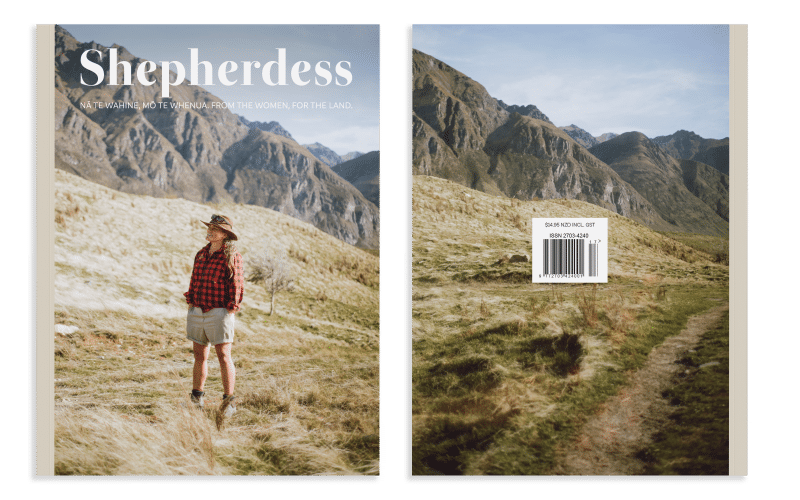

This story appeared in the Ngahuru Autumn 2022 Edition of Shepherdess.

Related Stories

Marie Kerapa

This story is the ninth in a series where we share, in their own words, the stories of ten women who call Tararua home.

Melissa Reiri

This story is the eighth in a series where we share, in their own words, the stories of ten women who call Tararua home.

Out Now

Seventeenth Edition

Our beautiful Ngahuru Autumn 2024 Edition is out now!