25 January 2023

Pooling their Waters

Toitū te Whenua, Toiora te Wai. Our Land and Water.

Writer: AS TOLD TO ANNA BRANKIN (KĀI TAHU, KĀTI MĀMOE)

Photographer: FRANCINE BOER

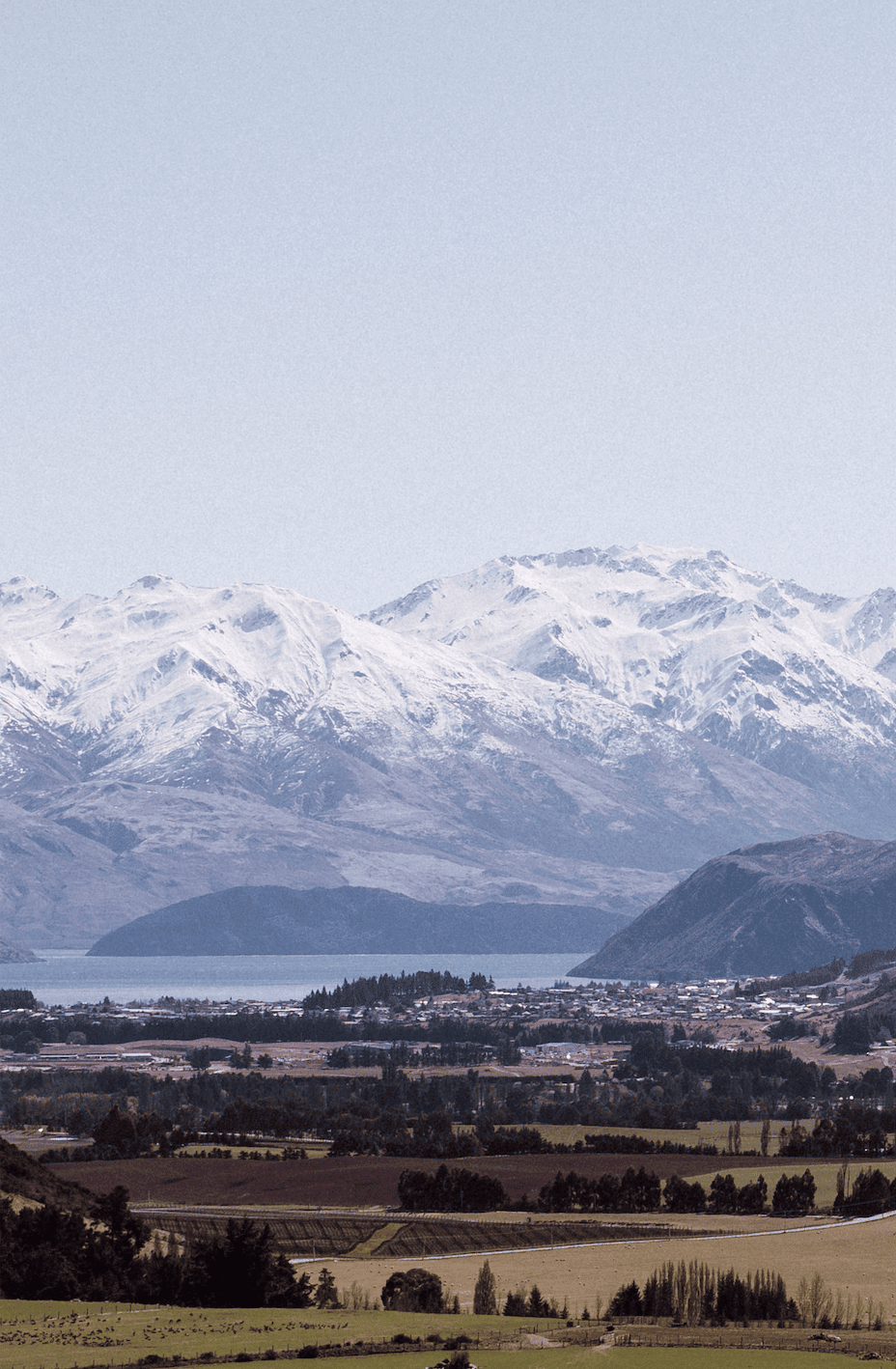

Te Taiao is the land, water, climate and biodiversity that contains and surrounds us all. From the mountains to the sea of the Upper Clutha catchment, the WAI Wānaka collective pools passionate people, resources and knowledge to drive healthy change in the environment, and create a place of belonging for all. Three women working with WAI Wānaka share what ties them to the land and drives their work.

“As I’ve grown up, and my children too, we’ve had the most magical times here. That started a really long, deep, passionate love of the region – of the water, the lakes, the rivers, the mountains.” Mandy Bell.

Mandy Bell, 57

WAI Wānaka Chair

I grew up on a farm in Mid Canterbury, and back then the whole family was very much part of the team. We’d ride the ponies and the horses to help bring the cattle in, we’d be in the sheepyards helping wherever it was needed, we’d be up at midnight if the rain was coming in, getting the small haybales into the hay barn. It was a pretty special upbringing and from that came a love of the land and a love of families on farms.

On top of that, my family has a really long connection with Wānaka. My grandparents bought a holiday house here back in the fifties, so my mother first started visiting some eighty years ago. My husband Jerry and I shifted back here thirty years ago when we bought Criffel Station from his family, just ten minutes outside of Wānaka, and this is where we raised our three children.

WAI Wānaka really came together as a group of entities that cared about this place and wanted to protect it. Beforehand, there were two separate groups: Guardians of Lake Wānaka and Lake Hāwea, and a group I was part of called the Upper Clutha Water Group. Within the basin there were thirteen projects underway. It was good research, but it was siloed. At the same time we were seeing an increase throughout the country in understanding the impact the primary sector was having on waterways. We were being told that Wānaka was going to double in size in the next ten years, and we were welcoming 1.4 million tourists to our town every year. There were a lot of pressures across our rural, urban and tourism activities.

We brought the two groups together in 2016 as WAI Wānaka and decided to look at where we wanted to be as a community in fifty years. We developed a community catchment plan that encompassed the whole basin: from the east end by the Luggate Bridge, cast your eyes around the mountain tops up to the [Makarore], across to the [Mātakitaki], Cardrona and back around.

After a lot of discussions the community came up with one simple aspiration: healthy ecosystems and community well- being for future generations. It sounds pretty basic, but however you look at it, it’s so meaningful. The next questions become: “What does healthy look like?” and “What does community well-being look like?” and “How do we get there?”

We started off thinking about water, and quickly realised that to look after the water brings in all these other benefits. We often use the analogy of riparian planting, which first and foremost is for water health. But it’s also positive for biodiversity on the land, and for greenhouse gas emissions into the air. That analogy applies to just about everything we do.

One of the key things we’ve seen is that once you help communities to understand our water and our biodiversity, and the impact our activities have on the environment, you start to get that change and that connection. And that’s really the heart of WAI Wānaka – connecting communities to take action to protect this special place.

Nina Rongokea, 30 (Kāi Tahu)

Field Supervisor and Health & Safety Rep

I first became involved with WAI Wānaka in January 2021 when I started working on their Jobs for Nature project. I had been wanting to leave the tourism industry and find work that aligned with my values, and then Covid hit and opportunities started popping up. It was the kick I needed to get out and find a gateway into the environmental space.

My family has whakapapa links to this area and we spent a lot of time in Te Waipounamu when I was a kid. Unfortunately, my grandad has passed on, but I’ve been lucky enough to have time with my uncle, Grandad's younger brother, but regrettably not lots. They grew up in Southland and listening to his stories about how things were when he was a kid and how helpless he felt being part of that generation where his culture was stripped away – that’s a big part of the reason I want to do this. My tīpuna didn’t have a chance to do this work and now I’ve got the opportunity to really do something and plant a seed for future generations.

One of the best parts about working in the field is being out there every day on farmland, meeting farmers and hearing their stories, hearing what they’re passionate about. Getting to know them and what they want for the future makes me feel really positive that this is the perfect area to have a pilot project like this. They all really care about freshwater quality. They all really care about the land. A lot of these large high country stations around here have been in families for generations and they all have such strong connection to the land.

And of course, this area is also really important to mana whenua. A lot of people don’t realise that, because there were no permanent settlements here. But there was a lot of seasonal occupation and some really significant mahinga kai sites. Understanding that history is the key to opening up the conversation about shared values and what can be done to future-proof and look after these areas.

Partnership and collaboration is the thing that gets me most excited about this project. It’s a long-overdue opportunity for iwi and landowners to work together towards a common goal. We all want healthy waterways and healthy land, but we’ve been looking at it and measuring it very differently. It will be really exciting to have that mātauranga Māori lens on environmental health and how we measure it.

This is one of the only projects focusing on the high country – there’s so much work happening on the coast. If we’re not doing our best up here, they’re just the last barrier before the ocean. That’s a discussion that’s gaining a lot of momentum and I feel really positive that in a few years it’s going to be right at the front of everyone’s mind.

Donelle Manihera, 37 (Ngāi Tahu)

Kauati

What’s really cool about WAI Wānaka is they’re sincere about developing relationships with mana whenua. They acknowledge there is much for them to learn, as individuals and as an organisation, and that’s made them a lovely group to work with.

I met the team at WAI Wānaka through my work at Kauati, who have been brought in to help build the foundational knowledge required for authentic relationships with mana whenua. Our starting point is to provide education across WAI Wānaka as a whole before specifically supporting the Our Land and Water project Knowledge for Action, which involves working with mana whenua. Kauati have been invited into this work by mana whenua entity Te Ao Mārama Inc to support WAI Wānaka on their journey.

When working in these spaces, we begin by understanding the needs of each party and designing our approach to fit. Our first session with WAI Wānaka focused on the history of Ngāi Tahu and Te Kerēme – the Ngāi Tahu Claim. For me, Te Kerēme teaches us about rights and interests, as well as the resilience of Ngāi Tahu. Fighting the Crown, over seven generations, is a vast undertaking. It’s a sobering and impressive story that speaks to the mana of Ngāi Tahu. Down here, effective iwi partnerships are recognition that all of that work was for something.

Our team at Kauati are cultural heritage and policy practitioners and this often sees us working between different knowledge systems. Much of our mahi is about bridging worldviews, and that is what I love most about this work. So much can be gained when we are curious to learn about another’s worldview – what do other cultures value? What is the context that defines their priorities? And how might this inform my understanding of place and people? For me, understanding multiple worldviews is powerful as a way to discover the core motivations that make us, and others, human.

Glossary. Iwi, a group of people descended from a common ancestor. Mahinga kai, traditional custom of gathering food. Mana, enduring mandate, authority and influence. Mana whenua, iwi or hapū who have whakapapa links, occupy and have authority to make decisions across an area. Mātauranga Māori, Māori knowledge system. Tīpuna, ancestors. Whakapapa, geneaology.

Revitalise Te Taiao is a research programme working alongside agribusinesses and communities in three locations as they progress land-use change, work with value chains and connect with markets to revitalise te Taiao. Head to ourlandandwater.nz/revitalise to learn more. This piece is the fourth in a series supported by the Our Land and Water National Science Challenge.

If you enjoyed this story, please share with someone else.

This story appeared in the Raumati Summer 2022/23 Edition of Shepherdess.

Get your hands on a copy.

Related Stories

An Ongoing Flame

For Winton couple Mikayla and Mitchell Smith, getting married was just another step in an already long and beautiful relationship.

A Decent Seed Cracker

Store-bought gluten-free or seed crackers are expensive, but homemade crackers are super easy to make and much more affordable.

Rewilding

Untouched World's new collection tells the story of letting nature back in and taking time to reconnect as the days get ever warmer and longer.

On My Wall

Sue Ross talks about the story behind this painting of a street scene of old Dubai that hangs on her wall.