Toi looks out the window of her bedroom. She has white hair, deep brown eyes and wears a long pounamu pendant around her neck. A colourful handmade quilt is draped over her bed. It's a warm day in Haruru Falls, the small village just west of Paihia where Toi lives. In the distance, the Waitangi River intertwines with the land and bush creating a vista of green and blue. A warm breeze moves through an open window, and Toi begins to tell her story.

"I started painting because I couldn't keep up with the images dancing in my mind. Painting was the quickest way to capture all of the ideas floating in my head. Both of my parents were artistic," she says, her words are precise and fast-paced. "I never thought of it as challenging. I just thought of it as blissful peace."

One of Toi's pieces hangs at the head of her bed. Embellished with distinctive red, yellow and black geometric triangles, it is one of the many artworks Toi has created that pays homage to the harakeke plant - or kōrari as it is known in Northland - that she adores and works with frequently. Her creations are dotted throughout the small, tidy home. Paintings, prints, carvings, muka, kete, jewellery. Now eighty-four years old, Toi has crafted her art using just about every medium possible; contemporising traditional frameworks as well as sifting ancient knowledge through several modern aesthetics.

But it was a chance encounter that led her towards visual storytelling and redirected the course of her life. "One of the best moments of my life was in 1976, when I went to the South Pacific Festival of Arts in Rotorua. My mother had wanted to go and asked me to go along with her. On the second day of the festival, we happened to take a wrong turn and walked right into the room where all of the weavers and Māori artists were," she says. "Even though my father had been a weaver, I had only learnt tāniko at boarding school, so I didn't know how to weave. I became completely intrigued and began talking to everyone in the room. That was the beginning."

Toi went on to become a distinguished creator of tāniko, korowai, whāriki and kete whakairo. She doesn't know who taught her father to weave, but she remembers coming home many times as a child and finding that the bath was full with harakeke floating in water. For several days, Toi and her siblings would have to bathe standing up in a large copper pot. But she loved the smell of the harakeke as her father worked the fibre, softening the leaves and cutting them to size.

At this time, European culture looked down on all things Te Ao Māori, including raranga, and Toi's father worried it would be held against her if she learnt the ancient practice. "I'd have to sneak in to be able to watch my father weaving," Toi says. "As soon as he became aware of me, he would throw what he was weaving over the back of the couch or send me to do a chore out of sight. He thought it would be better for me not to weave. I didn't understand it at the time, but it meant that the next time I gained an opportunity to learn, I would treasure it."

Orphaned at the age of fourteen, Toi's father struggled to find work when she was born, so the family moved up to Whangārei by her mother's grandfather, James Town. Her great-grandfather was a skilled blacksmith from Yorkshire, England, with a long moustache and a kind demeanour.

A few years later, they moved in with her mother's parents in Three Kings, Auckland. Toi's maternal grandfather, affectionately called "Grandpops," was an engineer and amateur artist who worked at the local cement works. It was here that she was told about the stone carved lions and gargoyles made by her ancestors, which still decorate several large estates in Yorkshire today, adding another layer of artistic nuance to her young mind. "My appreciation of colour grew, I think, from the old-fashioned laundry shed of my Grandpops," Toi says. "It was roughcast and there were bottles of all shapes and sizes. Light entered through the window and door, reflecting off the glass, filling the shed with a wonderful range of glowing colours."

Toi's mother worked in a railway goods office on the waterfront in Central Auckland but over the Christmas holidays she would take Toi and her sister Ngaio to stay in a batch on Waiheke Island. They would swim in the rain, take long walks in the bush and sit under their favourite pōhutukawa tree telling stories until they fell asleep. Driftwood and seashells were constant treasures, and they would study the clouds in the sky or the patterns in the sand made by the waves.

"My mother had a marvellous imagination," says Toi. "She instilled in me that nature is a marvel that we must treasure and care for. As a teenager, I began to realise how privileged I was to be a child of my parents - the term 'thinking inside the box' certainly didn't apply to them! My mother was an extraordinarily patient women and I can remember her happily sunning herself on the beach at Oriental Bay while Dad gathered pāua with his suit trousers rolled up to his knees."

Artistry runs in Toi's whakapapa. Her grandfather, Te Makarangi Te Rito, was a carver and maker of waka, like his grandfather, Ropatini Te Rito, who carved the palisade posts at Te Pāpāwai Marae in Wairarapa - one of the great meeting houses of the 19th century. Toi's father would paddle himself to and from school each day in a waka made by his father. "It was as if Dad was a part of the bush. He would teach me which berries to eat and show me how to harvest vines and leaves and barks for a hīnaki," Toi says. "One time, a storm meant we couldn't fish, but this didn't phase Dad. He quickly found a gull's nest and made a fire on the shore and boiled the eggs in seawater."

Light from the window falls across Toi's face as she leans forward to pull out a photo from a large box on the floor. The photo she holds up is of her mother and father. She smiles as the sun warms her face. There are many good memories in her box, of loved ones, exhibitions, many of the artworks she has created that have moved onto new homes. Toi has artwork held in collections at the Auckland Art Gallery, Te Papa Tongarewa and the Parliament Buildings in Wellington.

"I became obsessed with the idea that paintings could show movement. I painted one large piece called Uenuku after the carved god of Tainui. At the base, the colours were of the rainbow, strong because it had to balance out the top. Then the upward thrust that supported the moment of his head. I had woven it using squares instead of strokes. I painted the outlining holding my breath - I didn't know that painters used tape. I would often watch people as they viewed Uenuku, their heads whipping back as they went to move on, realising that they had seen it move when they weren't looking. I only finally sold the painting to the Waikato Museum after a series of strokes when I was eighty."

Toi shares many unique memories. How her paternal great-grandmother, Ani Mete, was a wonderful weaver too, who always slept in the wharepuni in Wairoa on spongey bracken and finely woven whāriki whakairo, even though her daughter had a newly built European-style home nearby. Toi's mother would recount how Nanny Ani, would sit outside on one of her mats, weaving in the shade beside the wharepuni. Her possessions were stored in kete that hung on the posts. "I was influenced by both of my parents and many people in my family - I didn't think anything of it!" she says. "I was fascinated when my father would gently coax lancewood saplings, his big strong hands disturbing as little as possible. Three or four season later he would harvest them, trim off the branches and begin to carve them into walking sticks. He always carved mokomoko, or lizards. He told me they were the kaitiaki of our hapū. Many years later, I was in the New Mexico desert at an ancient Indian village and a lizard ran in front of me. My Navajo friend who I was with told me that his people had never seen lizards in this part of the desert before."

A beautiful, handheld kete hangs at the end of Toi's small bed. It's vibrant colouring stands out against the pale walls of the room. This piece was made by a close friend Toi hasn't seen in many years, but the connection and the positive memories are still strongly imbued in the woven fibres. "We worked together for some time and she had an extraordinary power for helping people. Kete are a reminder that we must all come together to share our skills so that weaving can grow. One strand moving in this direction represents the man, and the other strand moving in that direction is the woman. Who is the stronger? Each are equally important. A kete is no use if its bottom is open so that has to be plaited together with care, so that what is placed inside remains there until it's needed. You cannot rush the handles because if they come apart, you lose all of the value."

She tells story after story. Too many to note here. Her beautiful, interwoven life, full of ups and downs, and so many magical moments. Her art an ode to the many facets of her life. Snapshots of the complex intricacies of this amazing woman.

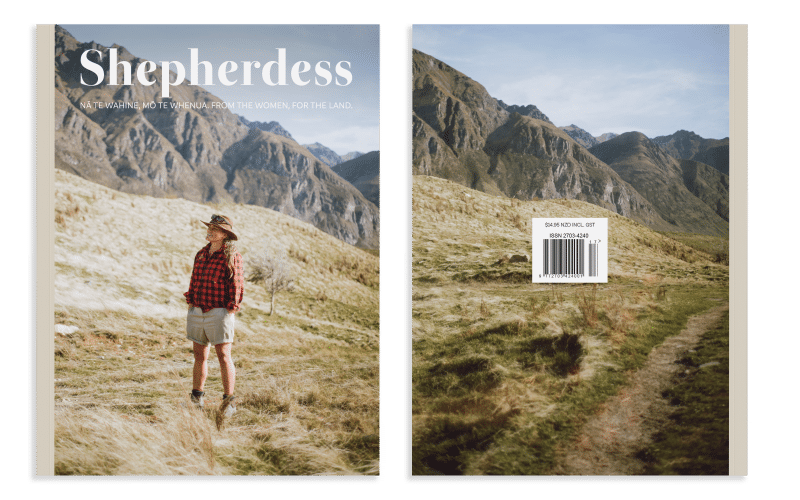

This story appeared in the Raumati Summer 2021/22 Edition of Shepherdess. Buy your copy through our web shop, or find your nearest stockist.

Related Stories

A Movement in the Māra

Bry Kopu, 51, and Te Raumahora Hema, 39, find synergy in their love for te taiao, and for their tūrangawaewae – Ngāmotu New Plymouth.

The Parenting Post

Dansy and Greg juggle their sheep and beef farm in St Arnaud, a building business in Māpua and Repost – a Marlborough-based recycled fencepost venture.

Trudy Hales

Trudy farms at Weber, half an hour from Dannevirke, with her husband Simon and boys Rocky and Alby. Here is Trudy's story, in her own words.

Summer Style

Shepherdess takes RB Sellars to West Wānaka Station with Samantha Goos and Nathan Roberts, who run Wānaka Horse Trekking amidst the majestic high-country scenery.

Out Now

Seventeenth Edition

Our beautiful Ngahuru Autumn 2024 Edition is out now!