16 October 2022

A good education: three different approaches to schooling from three rural families

WRITER: JESSICA DERMODY

Photographers: TESS CHARLES (SARAH ADAMS); CHARLIE HIGGISON (GEORGIE ARCHBOLD); MICHELLE MARSHALL (JORDAN CHITTY)

School is not always straightforward when you don’t live in a big city with plenty of options. Some choose to attend tiny country schools with rolls under ten, with all the charms they can bring, while others choose to homeschool, sometimes using correspondence school resources. Still others choose to board away from home in order to attend a bigger school that can offer wider opportunities. Shepherdess looks into three of the different schooling scenarios on the table for rural families and their children.

Sarah Adams, 40, has two children at Kākātahi Primary School in the Whanganui District. Over the past two years, she has helped the school’s new principal transform the tiny school, increasing enrolment numbers in order to keep it open.

Along State Highway 4 – a road more commonly known as ‘the Paraparas,’ which connects remote farming country between Whanganui and Raetihi – you’ll find a small but well-loved school by the name of Kākātahi. Here, Sarah and her two children, Molly, 9, and Freddy, 5, make up a good percentage of the total roll of eight students and five staff.

Sarah and her partner Justin have lived in the area – where he manages Papahaua Station, about 8,500 hectares owned by Ātihau-Whanganui Incorporation – for ten years. Molly originally attended a bigger primary school in the local town of Raetihi, however, a move to the tiny, rural Kākātahi Primary School, about twenty kilometres from home, was prompted when her then teacher, Charlotte von Pein – who Molly was flourishing under – started a new job as principal there at the end of 2021. “Running a small school takes someone pretty special, and she’s always going above and beyond to give the kids the best. Her own two girls go to boarding school in Napier, and they’re really nice girls who are always giving things their all. I think if that’s anything to go by, she’s clearly doing things right!” laughs Sarah.

But Sarah’s decision to move Molly from a bigger school to one where the entire school roll was less than half of her old class wasn’t easy. “To be honest, I wasn’t completely sold on the idea of tiny schools. There have been some moments where I’ve felt sad for Molly, that she might have a rough time missing her old friends that she’s known since preschool. We make a point of getting them around to stay the night,” says Sarah. Molly was joined this year by her younger brother, Freddy, and that was a much smoother experience – Freddy already knew most the kids from hanging out with Molly at the grounds. “It was hard watching the other kids from his day care go to another school, but he’s having a ball of a time now,” she laughs.

Kākātahi School is nearly an hour’s drive from Whanganui – where both Molly and Freddy do gymnastics – and twenty-five kilometres from Raetihi, where they go for pony club. Sarah sees the value in staying connected with the bigger community; she describes the weekly activities as a commitment, but just what “rural people have got to do.”

Sarah talks of a magical environment at the school, surrounded by rich countryside that’s incorporated into the children’s day-to-day lives. Charlotte has made it a “perfect learning environment,” she says. “She loves the outdoors and gardening, and is also married to a farmer, so the kids are outside most afternoons. They’ve cranked up the vegetable garden, planted heaps of native trees and they are currently learning about pests. It’s all relevant to their lives, and I think it’s so neat they’re learning that type of thing in school.”

Some may wonder about both children being in the same class, but it hasn’t been a problem yet, says Sarah. “They get on really well. Molly is very committed to school; she likes to do her best. Freddy is a little bit more of a show-off and can sometimes be quite loud. I think he gets a few eye rolls from his older sister,” she laughs. “There’s always something going on. The police called in the other day to show them things, and another person dropped in and donated fruit trees. The school is very good at thinking of activities that include all age groups.” There’s a good mixture of age and of boys and girls at the school, Sarah says.

Sarah describes Kākātahi as one big family. As well as the principal and a teacher aide, there’s also a cook. “She’s very nice to the kids on their birthdays and spoils them with cakes,” smiles Sarah. “She cooks them lunch every day and makes the occasional Milo, which is really neat. She uses the vegetables they grow in the school garden to cook with.”

Open since 1913, Kākātahi has long held a place in the farming district’s history, and as with most schools in New Zealand’s back country, keeping the doors open is a real community effort. Sarah plays her part in the operation of the tiny school, helping its “new era” with the upkeep of the grounds. The school has had a new lease of life in the last year, thanks to the passion of the principal and Sarah’s help. “It’s actually really fun to be part of making the school look awesome. The principal and I survey what we can change next,” she says. “The man who lives in the school house does the fencing and chops things down for us. The farmer over the road offers his tractor, and helped us with a gate the other week. It’s so cool to see the school looking nice from the community effort; there’s real pride in it from everyone involved.” And the increased effort is paying off – the previously struggling school has had a lot more families interested in enrolling their children. “I know of quite a few people whose kids are turning five next year, and they’re wanting to come. It’s really exciting,” she says.

Not only has the principal transformed the small school, but she has made life a little bit easier for Sarah, too. “We’re lucky that she comes past the end of our road most mornings, so she takes Molly and Freddy to school,” she says. The offer is a huge help for Sarah and her partner.

Freddy starting school has given Sarah more time and ignited an old passion – she’s gone back to studying. “I’m doing a short course in environmental management and if that goes well, which it is so far, then I’ll apply for a Bachelor of Applied Science or something along those lines. There are definitely days where I’m running to the car to get to the school in time for pick-up, but I’ve never been too late!” she laughs.

While the entire family is loving their involvement with the tiny school, boarding school is calling in the future. Sarah has no doubt that hostel life would be good for both Molly and Freddy. “I didn’t go to a boarding school, but lots of my friends did. I saw the positive impact it had when I linked back up with them at university when we all went flatting. They were so independent and worldly. I definitely think it’s the way to go,” she says.

Schooling is all in a day’s work for Georgie Archbold, 45, who teaches her two children at home through Te Aho o Te Kura Pounamu, formerly known as The Correspondence School.

Just east of Kahurangi National Park on Golden Bay’s West Coast, in the area of Paturau, Georgie teaches her two kids – Harrison, 10, and Annabelle, 9 – from her farmhouse kitchen table. Georgie and her husband Scott farm 1,500 hectares of sheep and beef country interspersed with native bush, sand dunes, scrub and stunning limestone formations, which provides hours of entertainment for the family, who moved there three years ago. The cost of such isolated beauty, however, is that attending the closest school – in the village of Collingwood – would mean an hour and a half return trip. “I thought that was too much time in the car, five days a week, on a road that’s dusty and windy,” Georgie explains. “I did correspondence school as a kid, and I had a magical childhood. So, we decided the kids should do Te Kura, rather than travelling all that way.”

Growing up on Rangitoto ki te Tonga d’Urville Island in the Marlborough Sounds, Georgie recounts her childhood schooling as being a time of freedom, with very little constraint. “We had to sit down and do school every morning, but by lunchtime the rest of the day was ours to help out on the farm, explore or have fun on the ponies,” she smiles.

The family follows a similar structure with Harrison and Annabelle now, although it took them a while to strike a balance between farm life and a homeschool routine. Both children had previously attended primary school in Mayfield, and the switch to Te Kura was “challenging”, Georgie says. “They loved school – they’re both really social children who love their sport and friends. The adjustment from that to just their mum and each other was hard. Being on a new farm, my husband needed our help and I felt really torn between teaching and helping on the property. The kids caught on to that, and would often ask to go out on the farm in the morning. That meant we wouldn’t get started with school until later in the day. But now my approach is that I have two jobs. My first and main priority is teaching, and we strictly start at 9am. My second is farming, so when school finishes at lunch we go help where needed. That change in mind-set has really helped us all.”

While Georgie has had her fair share of homeschooling experience, having been taught by her own mum (who often comes to stay with Georgie to help her out), she was blown away by how much has changed since her schooling days. “When the first lot of correspondence school work arrived here, I felt so overwhelmed. I had my own memories of it and hadn’t imagined the difference twenty-plus years would make. Of course things have changed, but it also seems a lot more complicated since I did it.” The experience has given Georgie a whole new appreciation of her own mum and school teachers. “When Mum was teaching us, we were far more isolated, with no computers or internet. I take my hat off to all those who balance school, work, farming and home life!” she laughs.

Making the most of afternoons on the farm is just as important as school in the morning for Georgie. Working as part of a team and being good communicators are two skills she highlights, and which Harrison and Annabelle have learnt from helping out their parents. “Around every corner on the farm there’s an adventure to be had. Experiencing that with our family is really special, and something I really valued from my upbringing. Replicating that with my children isn’t something I see as a disadvantage,” she says.

The decision to use Te Kura – where school resources are supplied and there’s a teacher based in Nelson that checks in with them and is available for help – was an easy decision for Georgie and her husband to make. “We went with Te Kura because I had a huge sense of responsibility to make sure my kids don’t go to high school and feel behind,” she says. While Te Kura work is mostly online, Georgie’s determined that her kids do most of their work by pen and paper. “There’s so much to be gained from the written word. So much is lost from looking at screens. I feel like the kids will have access to that when they go to high school.” Georgie’s passion for writing is evident; she’s the author of a children’s book, put together with her mum. She says the pair wrote Georgie is a Farmer as a fun way to teach kids where their food comes from and to show some of the positive aspects of farming.

While they love staying on the farm, the Archbolds make the trip into Golden Bay on Wednesdays during the winter months for rugby practice. Both Harrison and Annabelle play junior rubgy, and their dad is the coach. Saturday games can be up to three hours’ drive away, but Georgie says it’s important to keep their connection to the wider community. “The outings twice a week are good for the kids to get their social fix. It’s definitely a commitment, and it’s sometimes hard to juggle with the farm, but if we didn’t do it in those winter months then we wouldn’t probably go anywhere. It’s nice for all of us to meet people and the community to get to know us. Our grocery shop, which we do in Takaka, takes us a lot longer now because we stop so often to talk to people!”

Both Harrison and Annabelle will be going to boarding school in Nelson when they reach high school-age, carrying on a family tradition, says Georgie. Coming from a homeschooling background, she believes her life would have been drastically different had she not attended the hostel. “I was painfully shy, and would’ve happily stayed at home. Had I not pushed myself through those doors, I wouldn’t have made the friends I still have now, who have stood the test of time. My children on the other hand are so outgoing, and I know they will thrive at boarding school. The world is truly their oyster.”

Jordan Chitty, 17, grew up on a beef and dairy farm in Waihue, northwest of Dargaville, but for the past five years she has lived in Lupton House boarding accommodation while attending Whangārei Girls’ High School.

Jordan has made her room at the Whangārei Girls’ High School boarding house her own. There is a large wooden chest of drawers and photos of home, friends and family proudly grace the wall. “Being head prefect means I get the same room all year, and it’s nice to make it homely,” she says. “And an en suite is a big bonus!” She laughs. Having been at the hostel for the past five years means she’s had her fair share of different rooms, some with no door, or a wall that doesn’t go all the way to the ceiling. It’s all part of the boarding experience that many rural kids around the country can relate to, and it’s an experience Jordan loves.

Growing up on a 580 hectare dairy and beef farm about twenty minutes out of Dargaville, Jordan had a choice of their local high school or Whangārei Girls’, around an hour and a half away. “For me Whangārei was a better fit. I wanted different opportunities, and a clean slate. Going to boarding school provided that. I knew about two people at this school before I came, so there was heaps of opportunity to make new friends, like having a fresh start,” she remembers.

While moving to a new place was daunting, upon reflection Jordan’s now really proud of the collaboration between herself and her parents in making the decision. She thanks her “core class”– a concept at the school where the Year 9s stay in the same classes for the whole year – for making the friends she has today. “In my first term I sat beside a random girl and she’s been my best friend ever since,” she smiles.

Jordan lives in the hostel with roughly fifty other girls from Year 9 to 13. She says they “all get on like a house on fire,” but they all have their moments, too, of course. “At the end of the day, we all live with each other. We all have different personalities and we don’t get along all the time – and we don’t have too,” she says. The common bond shared between those living in a boarding house comes from the fact they’re all in the same situation together, Jordan explains. “There were eighteen of us in my year level that started five years ago. We’ve made so many memories, especially when we were younger.” The number is significantly lower now, with only three Year 13 students remaining at the hostel. The shrinking number is due to some having left high school, and others driving themselves in from home every day, she says.

Jordan’s role as hostel prefect means she has big responsibilities with the younger students, which she absolutely adores. “It’s like being a big sister. I’m always there for them and helping organise activities,” she says. While she’s now got forty-odd younger sisters to look out for, she does miss her sixteen-year-old brother back home, who chose to go to the local high school. “We are only a year apart, and I’ve missed growing up with him. He’s my only sibling but we’re very different people. He loves the farm, plays a heap of sport and has a really great friend group there, so for him it made sense to stay.”

Jordan has had another reason to miss home. “My mum had cancer a few years back, and it was really hard to be away from her during that time, while so much was happening. But thanks to technology, I could ring or FaceTime my family every night. I’m really lucky that they always make themselves free to catch up, and I always know they have my back,” she says. “If I ever really wanted to go home, they would come pick me up. Other than that, I don’t think I’ve missed out on too much at home.”

When she was younger, Jordan would go home every second weekend. Her grandparents or parents would come in to Whangārei, and she would get a ride home with them, or there was a shuttle she could take. She now goes home most weekends, as she has a job back in Dargaville.

Being a big sister to those at the hostel, especially the younger ones, has been one of the big drawcards for Jordan to return to the hostel, along with saving time on travel. “I enjoy coming back each year and helping the girls fit in. I’ve always found it easy to get along with the young ones. I love the vibe of the hostel, and I also get along well with the matrons [those employed by the school to look after the students]. If I didn’t get on so well with them, I don’t know if I would’ve come back. But the hostel is definitely the best place for me.”

Jordan will soon sit her final NCEA exams, and she’s got her sights set high for tertiary education. She’s applied for Otago University’s First Year Health Science programme, where she would eventually love to pursue a career in medicine. It’s a waiting game for Jordan at the moment – she’ll find out soon which hall of residence she’ll be in. Jordan thinks she’ll get on just fine living with all the other students in Dunedin, thanks to her hostel experience. “Being responsible for myself and my own actions for the past few years has made me really independent,” she says. Like when she started high school, Jordan doesn’t know many people who are making the trip south for the next chapter of their lives, but she’s been in this position before. “I’ll still miss my family, and they won’t be an hour’s drive away anymore – rather a few flights away. But I do think the hostel has equipped me for university life and I feel a lot better than I might going straight from home,” she says.

This story is part of THREAD, a year-long project by Shepherdess made possible thanks to the Public Interest Journalism Fund through NZ On Air.

If you enjoyed this story, please share with someone else.

Get your hands on a copy of Shepherdess.

Related Stories

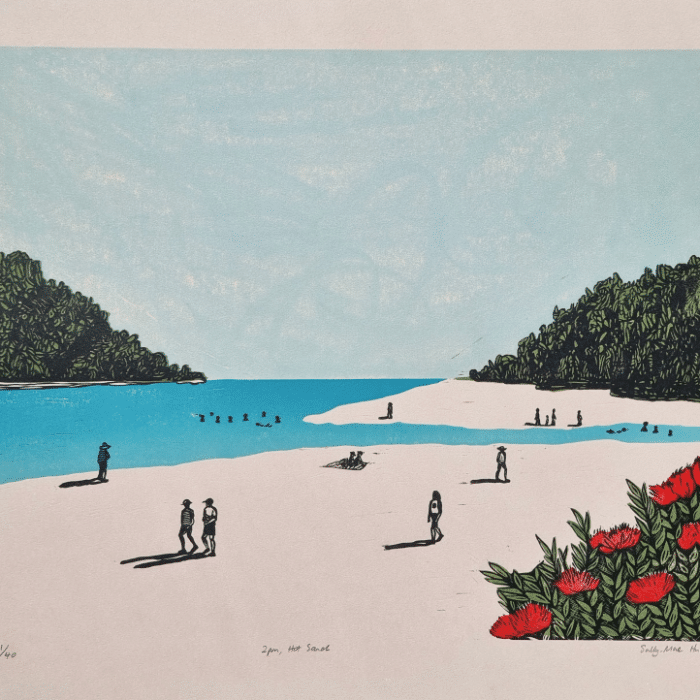

The Gallery, Raumati Summer 2023/24

2pm, Hot Sand by Sally-Mae Hudson, linocut print 50cm x 38cm (limited edition of forty).

Sharon Smith

This story is the first in a series where we share, in their own words, the stories of ten women who call Tararua home.

Slow Stitches

Self-taught fibre artist Fleur Woods is crazy about the chaotic creative process. From her eclectic home in Upper Moutere, she surrounds herself with colourful fabrics and threads, combining them with